No one in history has made people laugh as much as Charlie Chaplin. The Little Tramp was silent cinema's first mega star, a character so recognizable that The Guardian has called him 'the most famous man who ever lived.' Even today, there are people living in random, out-of-the-way places from Albania to Eritrea to inner Mongolia who would still be able to tell you Chaplin's name just from glancing at a picture of him. That was the power of Chaplin's timeless comedy: He could make you continue to associate things like toothbrush mustaches with laughter even after Adolf Hitler had ruined them for everyone.

The Complete Charlie Chaplin Filmography (1914-1967) Menu. Release Calendar DVD & Blu-ray Releases Top Rated Movies Most Popular Movies Browse Movies by Genre Top Box Office Showtimes & Tickets Showtimes & Tickets In Theaters Coming Soon Coming Soon Movie News India Movie Spotlight. Chaplin Multimedia is a web design agency passionate about web site design. For over 19 years we have been working hard for our clients making their businesses run more efficiently online. If you are looking to increase your sales or get your message across effectively using the Internet, we look forward to working with you. Charlie Chaplin Dokumentation. Charlie Chaplin Dokumentation.

Yet Chaplin's real life was as far from a laugh a minute as you can possibly get. While his films have been criticized in our cynical modern world for a tendency toward saccharin sweetness and blatant tear jerking, the guy dreaming up all this schmaltz was far from smiling on the inside. From his early years trapped in biting poverty in London to his later mauling by the American political establishment and his own inability to say no to his darkest temptations, Charlie Chaplin was a clown who wasn't just crying behind the facepaint, but screaming his way through an absurdly bleak existence.

His alcoholic father abandoned him

In 1890, Charles Chaplin was one of the hottest talents on the British stage. A comic singer, he was going up in the world even as he was settling down with his wife Hannah — a fellow vaudeville star — and their baby Charlie. Yep, Charlie Chaplin was actually the second celebrity to bear the name, after his own father. It might have been an honor, had Charles Chaplin the elder not been permanently soused.

The official Charlie Chaplin website tells the story. Drinking was a big problem among vaudeville stars in the 1890s, and Charles Chaplin was a boozehound like no other. By the time Charlie was 12, the old drunk was dead, killed by his addiction to the bottle. If this sounds tragic, now might be the time to mention that it was probably better that way. Charles was awful. When Charlie was just 1, he walked out on the family, taking their means of support with him. Hannah and Charlie were plunged into grinding poverty, which Charles did nothing to alleviate. When he was at the height of his fame, presumably earning decent money, he was arrested for failing to provide for both Charlie and his other son, Sydney.

Despite their destitution, Hannah managed to keep a roof over young Charlie's head and entertained him with old vaudeville routines. It could have even been a 'poor but happy' childhood. As you're about to see, though, almost nothing in Charlie's life qualified as happy.

A mother's madness

'Be careful what you wish for' goes the adage, and it's probably never been as apt as it was for young Charlie Chaplin. Always fascinated by his mother's vaudeville career, Charlie was mimicking her routines by the age of 5. It's not hard to imagine the boy wishing he could join her onstage. If that's the case, his wish came true in the worst way possible.

It happened during one of Hannah's performances, while Charlie watched from the wings. According to Biography, Hannah was halfway through a song when she suddenly lost her voice. The manager panicked and shoved Charlie out. In what feels like the opening for a feel-good movie, young Charlie knocked everyone's socks off. In a kinder world, this moment would be the beginning of Charlie's career. Instead, it was the beginning of his mother's descent into madness.

It quickly became clear that Hannah's voice issue was just the first outward sign of the demons consuming her. As she kept trying to raise her kids in poverty, she drifted further from reality. Eventually, she was institutionalized. This being Victorian London, the 'social safety net' was something tramps caught fish with. Charlie and Sydney got chucked into the workhouse, which was exactly as Dickensian as it sounds. Charles Sr. did briefly agree to take the boys in, but it didn't last. Charlie would wind up spending so much of his childhood in the workhouse that he only ever received six months' schooling.

Endless, awful jobs

For the first 12 years of Charlie's life, Charles seems to have had fleeting pangs of conscience when he tried to help his kid, even if those pangs quickly vanished beneath a sea of booze. One such moment came in 1897, when the official Chaplin website claims he got his son into a clog dancing troupe to make ends meet. (Even this is uncertain. Other sources claim Hannah's sympathetic showbiz contacts arranged the gig.)

Given that you're reading an article on Charlie Chaplin, famous actor-director, rather than Charlie Chaplin, non-famous Victorian who died in poverty, you might be expecting to read that this, finally, was Charlie's big break. But since when did fate make anything easy for young Charlie? The Eight Lancashire Lads went nowhere, and Charlie was forced to scramble for work to survive. According to Biography, this meant taking on an endless parade of awful jobs.

Charlie would later claim he'd been a newspaper vendor, a toymaker, a printer, a doctor's boy, and about a zillion other things. It wasn't until the 20th century that he was able to move back into vaudeville, and it wasn't until 1908, when he was 18, that it became a viable career. Signed to play the drunk in a comic sketch for Fred Karno's pantomime troupe, Chaplin even toured America. Evidently, America liked what it saw. In 1912, producer Mack Senett signed the young comic to appear in motion pictures. This time, the big break was real.

The tyrant appears

Stanley Kubrick's name is a byword for artistic perfectionism to the point of insanity. Before Kubrick became the poster boy for tyrannical directors, though, there was Charlie Chaplin. After Senett signed Chaplin, the young comic's star exploded. According to the British Film Institute, Chaplin made 34 films in 1914 alone. By the second film, he'd created the Tramp character. By the 12th, he was directing. By 1915, he'd signed to Essanay Studios and been given his own production unit. By 1916, he was with Mutual Films, where he had complete creative freedom and the largest salary in Hollywood.

So, yeah, things were kinda going great for Chaplin, and they would continue to for the next few years. But this was also the period where Chaplin the crazy-on-set autocrat emerged. It would be the world's first real glimpse of the tortured, driven man behind the genius.

PBS has the details. Chaplin on set was a Chaplin obsessed. Known as the most demanding man in Hollywood, Chaplin would reshoot each scene hundreds of times. Rather than directing, he'd act out everyone's role for them, then say 'do that.' (Many years later, on 1967's A Countess From Hong Kong, Tippi Hedren claimed this drove Marlon Brando crazy.) He would fire actors halfway through and start the film afresh, with all the bazillions of takes this implied. It was an insane system, but it worked. It also set the stage for the even darker Chaplin who would soon emerge.

Controversial marriages and unhappy allegations

By 1918, Chaplin was running his own production company, First National, and making films that are still considered classics today, like The Kid. Unfortunately, this is also when Chaplin's darkest side emerged. He began serially seducing young girls.

Vice has the story. Mildred Harris was barely 16 when Chaplin met her, and at best an emerging starlet when Chaplin was the biggest star of all. He seduced her, thought he'd gotten her pregnant, and arranged a hasty marriage. When he found out the pregnancy wasn't real, he got her pregnant for real and then divorced her.

Maybe it was his father's inspiration, but Chaplin's next love would be even darker. He first met Lita Grey (above) when she was a 12-year-old child star in 1920, and spent the next few years doting on her, keeping her in his orbit until she was finally of age — maybe. In 2015 the Times of London claimed Grey was 15 when Chaplin seduced her, instead of the widely reported 16. Either way, he got her pregnant, married her, impregnated her again, and abandoned her in 1927.

There were other scandals in Chaplin's love life, too. The 1924 shooting death of producer Thomas Ince on William Randolph Hearst's yacht was rumored to be the result of Hearst trying to kill Chaplin for seducing his wife but accidentally shooting the wrong man. In a taste of things to come, Biography claims these seductions and salacious rumors would later see Chaplin banned from several states.

'Deeply dumb in many ways'

Despite the darkness of his private life, this period of Chaplin's career was conversely when his artistic light shone its brightest. In 1919, Chaplin set up United Artists with D.W. Griffith and Mary Pickford (via The Guardian), where he went on to make films that still define silent cinema, like The Gold Rush. But it was when the Great Depression hit that Chaplin reached his peak. For weary audiences, the Tramp was the tonic they needed. City Lights and Modern Times really did fulfill that old cliche of bringing joy to millions, even as other silent stars like Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton faded away.

Charles Chaplin Jr

By the outbreak of World War II, Chaplin wasn't just famous. He was an icon. A man who considered himself untouchable, which may explain what happened next. As the war got underway, Chaplin began making public speeches extolling the Soviet Union. According to Slate, in 1942 he praised Stalin's purges and said 'the only people who object to Communism ... are Nazi agents.'

Years later, Orson Welles, who worked with Chaplin on Monsieur Verdoux, would call him 'deeply dumb in many ways.' He could have been talking about Chaplin's Communist speeches. With the establishment already against him over his private life and perceived 'anti-Americanness' — including J. Edgar Hoover and gossip columnist Hedda Hopper — Chaplin had handed his enemies the stick to beat him with, then turned around and dropped his pants, too. The results would be anything but amusing.

Failed paternity and 'white slavery'

You're about to embark on the really, really tragic part of Chaplin's life. But, first, you need to hear about the Mann Act. Ushered into law in 1910 by Rep. James R. Mann, the act's official name is the White Slave Traffic Act, and its intention was to combat forced prostitution (via NPR). However, as History details, the act was worded so broadly that it could be used to prosecute almost any consensual sex act, provided one participant traveled to meet the other.

In 1944, Chaplin's personal life again exploded in a mess of seedy allegations, this time for supposedly impregnating and dumping actress Joan Barry. Previously, this would have stayed in the tabloids. But, emboldened by rising anti-Communist feeling in America, this time the establishment pounced. Chaplin was arrested for 'white slavery' under the Mann Act, having allegedly taken Barry across state lines before seducing her. He was eventually acquitted, but the establishment was gunning for his blood.

Chaplin was sued by Barry for paternity payments. Despite medical tests that proved he wasn't the father, Barry won her case and Chaplin was forced to pay out for a kid that was scientifically proven to belong to someone else. What remained of his reputation in America was shredded. But it was activity in Washington D.C. that would really doom the Tramp. Specifically, the ironically un-American activities of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and its witchfinder general Joe McCarthy.

The colossal flop

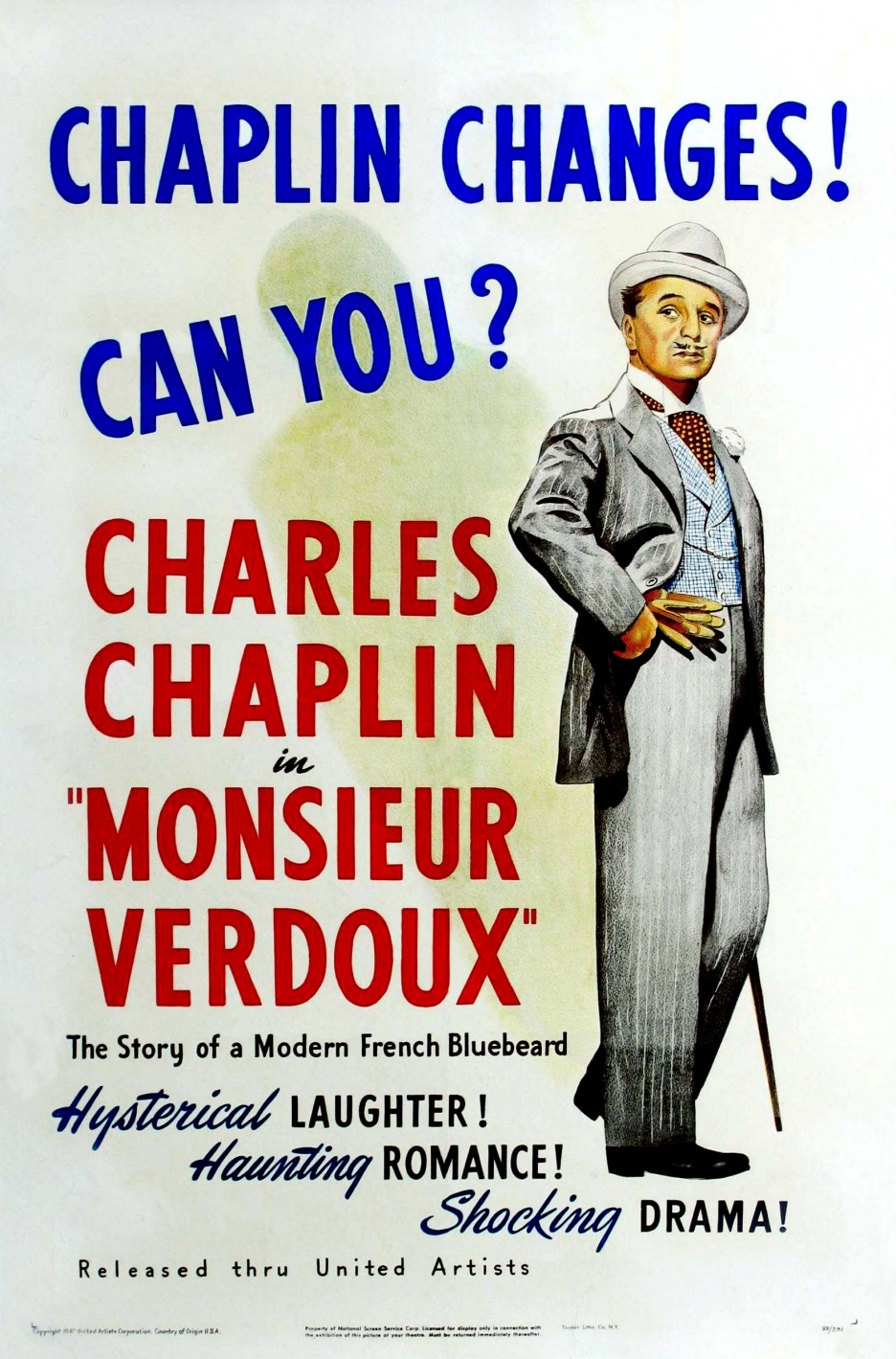

Let's pause here and take stock. It's 1947. Chaplin's reputation has been ruined by scandal and an unfortunate pro-Communist streak. Europe is shattered by war, America is devouring itself in a Red Scare, and all audiences want is for the Little Tramp to make them laugh again. Instead, Chaplin chooses to make Monsieur Verdoux, an Orson Welles-scripted black comedy in which Chaplin plays a serial killer (pictured above) preying on rich old ladies. You can probably already guess the public reaction.

Monsieur Verdoux bombed hard. It nearly ruined United Artists. As Slate describes, the press junket for the film turned into a kangaroo court in which Chaplin was metaphorically lynched. The tabloids had announced in advance that they would make him squirm for his Communist leanings and, boy, did they ever. Chaplin almost had to abandon one press conference when all reporters did was accuse him of not being sufficiently supportive of capitalism. It didn't help that Monsieur Verdoux could clearly be read as a black satire on capitalism's worst excesses.

At the exact same time Monsieur Verdoux was ruining his career, Chaplin was put on notice by HUAC that he could soon be indicted. While he never was, the Little Tramp still became a favorite punching bag of senators like William Langer, who divided his time between demanding Chaplin be deported and trying to get Nazi war criminals off the hook. In the backward world of McCarthy America, it was Langer who emerged victorious.

Blacklist and exile

Although never formally indicted by HUAC, Chaplin was still blacklisted. Blacklisting ruined guys like Dalton Trumbo, but Chaplin was somewhat immune. He was rich enough to finance his own films, he owned a distribution company, and he was still popular enough that a group of followers would always watch whatever he made. Which may be why the aftermath of Monsieur Verdoux saw him back directing his last masterpiece, Limelight. While America had clearly had enough of Chaplin, Chaplin's fame allowed him to go on working ... right until he got kicked out of the USA.

BBC has the details. Although he'd been living in America for 40 years, by 1952 Chaplin hadn't applied for U.S. citizenship. He was still clutching his U.K. passport, which didn't endear him one bit to guys like William Langer. In the fall of that year, Chaplin decided to combine an international press junket for Limelight with a trip to Britain. He planned to be in Europe about four weeks. He wound up living there for 25 years.

On September 19, U.S. Immigration barred Chaplin from re-entry. Chaplin had given America claim to the greatest ever on-screen character, he'd elevated Hollywood movies into an art form, he'd helped millions forget their woes and, in return, he'd been vilified and ejected from his adopted home. He'd only ever return once. For the rest of his life, Chaplin was a man in exile.

His body was stolen after he died

The last decades of Charlie Chaplin's life consisted of crazy ups and downs. On the one hand, he only made two more films – A King in New York and A Countess from Hong Kong. (King was banned in the USA for being 'anti-American.') On the other, he settled in Switzerland with his wife, Oona, and raised a remarkably happy family, according to his son. That's surprising because Oona was another of Chaplin's young conquests. Married when she was 18 and he 54, they nonetheless stayed together until Chaplin died in 1977.

It would be nice to end Chaplin's story like that, with some semblance of peace after a hard life. But fate had one last, gruesome curveball to throw. Months after his funeral, two graverobbers dug up Charlie's body and made off with it. They held the Tramp's remains for 11 weeks, demanding a ransom payment of $600,000 (via Smithsonian).

But Oona was apparently made of steel because she refused to play ball, hanging up on the criminals rather than hear their demands. Panicked, the ghouls got sloppy, and Swiss police tracked them down. After a tortured life and a bizarre postscript, Chaplin was finally laid to rest, for good this time. He may have had a hard time, and he may have done some unpleasant things, but the Tramp is generally remembered for his laughter and his artistry, rather than his difficult life. He probably wouldn't have wanted it any other way.

Introduction

The credit title on City Lights, “Music composed by Charles Chaplin”, brought a surprised and indulgent raising of eyebrows. Because of the occurrence of phrases, here and there, from some familiar melodies, inserted, in most cases, for comic effect, and the use of “La Violetera” (“Who’ll Buy My Violets” by José Padilla) as a theme for the blind flower girl, Chaplin was assumed, by some, to be stretching his claim to everything in the film.

Attitudes changed with the subsequent appearances of Chaplin scores in “Modern Times”, “The Great Dictator”, and “Monsieur Verdoux” (The two latter talkies with occasional musical interludes and “background music”), and with the full score for the reissued “The Gold Rush”. A quality, which can only be described as “Chaplinesque” was discerned and commented upon in this music, despite the fact that it was arranged and orchestrated by other hands.

Those who still believe that Chaplin merely hummed a tune ot two and that “real musicians” did the rest have only to listen to the scores of several of his films. The style is marked and individual. It shows a fondness for romantic waltz hesitations played in very rubato time, lively numbers in two-four time which might be called “promenade themes”, and tangos with a strong beat.

It can now be seen that Chaplin’s music is an integral part of his film conceptions. In similar fashion D.W Griffith also composed some musical themes for his pictures. But perhaps of no other one man can it be said that he wrote, directed, acted, and scored a motion picture.

Incidentally, Chaplin even conducted the orchestra, himself, during recordings, an added reason for the satisfying impression of wholeness in the Chaplin films.

Music through his Life

Although musically untrained, Chaplin nevertheless has the advantages of a musical inheritance from his ballad-singer father, the natural endowment of a quick ear, and a superb sense of rhythm, a taste for the art, experience with it on the stage, and an amateur performer’s devotion to it.

In “My Trip Abroad” there is a passage describing his first consciousness of music. As a boy, in Kennington Cross, he was enraptured by a weird duet on clarinet and harmonica, to a tune he later identified as the popular song, “The Honeysuckle and the bee”. “It was played with such feeling that I became conscious, for the first time, of what melody really was”

According to Fred Karno’s biography, young Chaplin spent much of his leisure time between shows picking out tunes on an old cello. When Chaplin was signed by the Essanay Company, he bought a violin on which he scraped for hours at night, to the annoyance of less wakeful actors when they all lived next to the studio at Niles, California.

Lita Grey

While he was being feted during the negociations with the Mutual Company in New York, Chaplin, appearing at a benefit concert at the old Hippodrome (February 20, 1916), led Sousa’s band in the “Poet and Peasant” overture and his own composition “The Peace Patrol”. That same year Chaplin published two songs “Oh! That Cello” and “There’s Always One You Can’t Forget”, which was a musical tribute to his first romance.

In the twenties he made records of his “Sing a song” and “With you, Dear, in Bombay”, both later used in the sound version of “The Gold Rush”. Subsequent years saw the publication of a theme from “The Great Dictator” to a lyric entitled “Falling Star”, and three numbers from “Monsieur Verdoux” : “A Paris Boulevard”, “Tango Bitterness”, and “Rumba”.

After Chaplin made his first million, he installed a pipe organ in his Beverly Hills mansion. In certain moods he is known to have fingered this expensive instrument for hours at a time. Realizing the importance of musical accompaniment to the silent film, Chaplin sought to have it reproduced in every theatre exactly as he wished it. He supervised the cue sheets (lists of numbers to be played, sent free to all theatres booking a film) of his pictures from “The Kid” (1921) up to “City Lights” (1931) – when it was possible to have the music recorded on the film itself. Then it also was commercially expedient to claim at least “music and sound effects” since by 1931 the silent picture has been superseded by the talkie.

The Music of City Lights

Arthur Johnston and Alfred Newman arranged and orchestrated the music for “City Lights”, Chaplin’s outstanding score. But the melodies, with the exceptions noted above, used for the associations they would evoke, were composed by Chaplin. At least twenty numbers in the score could be published as separate and original works. As was customary in the scoring for silent pictures, the Wagnerian leitmotiv system was followed – a distinctive musical theme associated with which character and idea. The musical cues in “City Lights” come to some ninety-five, not accounting the passages where the music follows or mimics the action in what is generally known as “mickey-mousing” from its use in the scoring of animated cartoons.

A fanfare on trumpets, over a night scene, opens the picture proper.It is heard again as a sort of fate theme at moments of crises, such as the count over Charlie in the boxing ring, and his capture and imprisonment. Saxophone bleating, in slightly off synchronization with the lips, mimics the speakers at the unveiling of the moment. This shrill squeaking is used not only as a comic note itself, but as a burlesque of the talkies. When Charlie is ordered down, a bustling “galop” number in G minorn, played in fast tempo, accompanies his scrambling over the statues. The Tramp’s wanderings through the city streets are accompanied by a gallant bitter-sweet melody mostly on the cello. The theme is repeated seven times when he is in hopeful moods. The flower girl’s principal theme is José Padilla’s “La Violetera”, and phrases of it are played behind the Tramp, when it is pertinent to indicate that his thoughts dwell on her. She had two subsidiary themes, one a pathetique for scenes in her slum room, and the other a violin caprice, for her wistful moments.

The music behind the tramp’s meeting with the eccentric millionaire is an amusing burlesque of opera. A dramatic theme introduces him and is followed by an over-dramatic agitato as he ties the suicide noose. Charlie’s dissuasions are musically rendered in burlesqued opera recitative. Another kind of music is kidded in the accompaniment to Charlie’s promise that “Tomorrow the birds will sing” – the “April-showers, silver-lining, rainbow-round-my-shoulder” sort of “theme song” that echoed through early talkies, particularly in the Al Jolson films. In later sequences the tramp has only to point upward in mock-heroic fashion; no title is necessary, the music “tells” what he is saying.

The nightclub music for the “burning up the town” is a hectic jazz theme with a long sustained high note and marked rhythm. A rumba-like number accompanies the party scene where the tramp swallows the whistle. When the millionaire wakes sober, to find a stranger sharing his bed, there is a snatch of Rimsky-Korsakov’s ballet “Scheherazade” – played in duet form – in low register for the perplexed millionaire and high for the tramp. In like manner bits of “How dry I am”, “I hear you calling me”, etc…are called upon for comic comments.

There are two love themes – one a light romantic waltz played very rubato to action, and a tragic piece associated with the Tramp’s hopeless love. Played also behind the tragic of the picture, with its grim and fateful chords, the second has a distinct Puccini flavor.

A sprightly theme on the bassoon accompanies many of the tramp’s more humorous moments, such as his mishaps behind the streetcleaner’s cart; and there is a singularly amusing use of a tango during the boxing sequence. The fight itself is underlined by a feverish musical “hurry”, also used behind other fast action.

It is true that one or two of the minor numbers are reminiscent. A short dance piece resembles “I want to be happy”. The famous apache dance is a paraphrase. The crooked-fighter theme sounds a bit like “Lock Cut for Jimmy Valentine”. Some Debussy chords herald the morning, and the “Second Hungarian Rhapsody” is cleverly jazzed up for a little chase scene. A film eighty-seven minutes long calls for a score of about a hundred and fifty pages and a little “borrowing” here and there can be overlooked.

“City Lights” ends with the following music. The tramp, let out of prison, searches for the blind girl.

Sequence: Cue 91. Tramp comes to corner where Girl used to sell flowers

Music: “La Violetera” by José Padilla (Played slowly)

Sequence: Cue 92. Tramp wanders the streets…

Music: Tramp Theme (played slowly and tragically)

Sequence: Cue 93. Tramp finds flowers in gutter…

Music: “La Violetera” by José Padilla (normal tempo)

Sequence: Cue 94. He turns to the girl in the window of her shop laughing at him…

Music: Violin Caprice (secondary girl theme)

Sequence: Cue 95. Girl touches hand of tramp…

Music: Tragic love theme

Incidentally, sound effects are sparingly used, and then only for deliberately pointed effects, like the swallowed whistly, bells, the firing of revolvers etc… Falls and blows are not accented by traps, nor are there the other tasteless noises by ratchets, etc…that have featured so many “revivals with sound added”, copies from the distracting technique of sound cartoons. Above all, the human voice is not employed, an artistic mistake too often made in attempts to bring old silent pictures “up to date”.

Oona O'neill

The haunting and pleasant Chaplin melodies in “City Lights” are pleasing in themselves, but the picture is one of the few extant examples of the silent medium’s power when wedded to a musical score which properly interprets the action and heightens the emotion. The legend has grown that silent pictures were accompanied by a thinkling piano, either played thumpily in the so-called “nickelodeon” manner, or in a more dignified, but essentially neutral style. Actually, from 1914 on, every town of five thousand or over had at least a three-piece orchestra – or an organ. The Griffith and Fairbanks films, specials like “The Covered Wagon” and “The Big parade”, all had orchestras travelling with them, playing scores as carefully worked out as “City Lights”.

By strict musical standards Chaplin’s score may not equal those of Virgil Thompson, Max Steiner, Georges Auric or William Walton. Thompson’s scoring for “The River” and “Louisiana Story”, with extremely clever arrangements of old folk tunes, is far more sophisticated and intellectual. Nor does Chaplin possess the virtuosity and present grandiose manner of Steiner, where too often sheer bombast attempts to make up for the emotional vacuity in the picture itself. But who, better than Chaplin, could point up musically the tragic-comic adventures of the tramp character he himself created ?

Video Charlie Chaplin Multimediaal

Extract from « Charlie Chaplin » by Theodore Huff, published by Henry Schuman Inc., New York 1951. Chapter XXV, Chaplin as a Composer